The Leagues Are Long Gone, But The Cards Live On – Alternative pro football leagues seem to pop up every few years with the promise of capturing NFL-sized success or serving as a feeder league. The leagues reflect a Siren’s call for wishful investors and a fresh chance for football players hoping to reach or return to the sport’s biggest stage.

Some leagues have found success, such as the Canadian Football League and Arena Football League, which have been around for decades. The All-America Football Conference saw three of its teams admitted to the NFL, while the American Football League merged with the NFL.

Many other leagues have failed. The WFL, USFL, WLAF/NFL Europe/NFL Europa, XFL and AAF all followed a similar pattern. Founders promised an NFL addition or alternative — more football. Rosters filled with a mix of NFL washouts, underrated talent and former college standouts. Big-name coaches and executives brought credibility and name recognition. Teams were given splashy names, some of which made little sense (Shreveport Steamer? Montreal Machine? Orlando Apollos?). A few teams established intense fan support. Others played to near-empty stadiums and bounced from city to city, resembling a traveling circus before vanishing.

The failed leagues all caved amid mounting financial issues. Beyond memories and YouTube clips, the most tangible reminder that the leagues existed are the cards — aspirational and fascinating card releases that contribute to the fabric of professional football.

Ripping wax from the defunct leagues is an exercise in volatility. Many of the teams depicted (as well as some of the card manufacturers themselves) disappeared within a few years of the cards being produced.

Players who starred in the failed leagues went on to achieve their football dreams — a path former Alliance of American Football players are currently trying to follow after the league folded in April. For others, the cards marked a final hurrah before the subjects became high school coaches and business executives and pastors and salesmen and plumbers and broadcasters.

***

Stan Gelbaugh was content selling copiers and fax machines.

The NFL also-ran was ready to call it a career after backing up Jim Kelly for the Bills from 1986-89 and later getting cut by the Bengals, who had another solid quarterback in Boomer Esiason, like Gelbaugh a University of Maryland product.

“I thought I was done with football,” Gelbaugh said in a recent interview.

And then the phone rang. It was Jim Haslett, his former Bills teammate, who had become the defensive coordinator of the Sacramento Surge of the World League of American Football. The NFL-backed WLAF was set to begin play in March 1991, serving as a spring developmental league showcasing football talent across two continents.

Gelbaugh went to World League training camp expecting to join the Surge. But after the league’s supplemental draft, he learned he was instead headed to London to play for the Monarchs — London’s GM was Billy Hicks, a former employee for the Dallas Cowboys, the NFL team that drafted Gelbaugh in 1986.

“He was ‘The Turk’ in Dallas,” Gelbaugh said of Hicks. “He actually cut me when I was a rookie.”

Another bad omen: by the time Gelbaugh joined his new team, the Monarchs had already selected an offensive captain: John Witkowski, the former Detroit Lions QB.

Gelbaugh was the backup again. And this time he was more than 3,000 miles away from home, on a different continent, in a new league, making a fraction of an NFL salary.

Gelbaugh was London’s backup for one half.

Witkowski started the team’s first game and struggled, and by halftime he was benched in favor of Gelbaugh. In the third quarter, Gelbaugh connected with Jon Horton on a 96-yard touchdown pass, and London beat the Frankfurt Galaxy 24-11.

Gelbaugh was the starter the rest of the way for head coach Larry Kennan, leading the team to a 9-1 regular season record and the first World Bowl title. His stat line: 2,655 yards, 17 touchdowns, a 92.8 passer rating. For his efforts, Gelbaugh was named the league’s offensive most valuable player.

London’s success was a team effort. The offense was anchored by the offensive line, nicknamed the “Nasty Boyz,” which only allowed 10 sacks on the season. Tackle Steve Gabbard, guard Paul Berardelli, and center Doug Marrone — now the Jacksonville Jaguars’ head coach — were All-World League first team selections, while tackle Theo Adams made second team.

Other standout players on defense included cornerback Danny Crossman, MVP of the World Bowl and a longtime NFL coach, and safety Dedrick Dodge, who won Super Bowl rings with the San Francisco 49ers and Denver Broncos during the 1990s.

“We had a squad of guys who were hungry and wanted to get back to the NFL if they could, or get a shot in the NFL,” Gelbaugh said. “It was very competitive. I remember we couldn’t even practice sometimes because the offensive and defensive guys would be fighting each other.”

The Monarchs weren’t a one-note team. Before the 21-0 World Bowl win over the Barcelona Dragons, dozens of London’s players and cheerleaders (known as the “Crown Jewels”) recorded a song, “Yo, Go Monarchs,” in the spirit of the Chicago Bears’ “Super Bowl Shuffle.”

The song, full of guitar riffs, inside jokes and braggadocious lines — Stan the Man puts the ball in motion/And the Nasty Boyz gonna start a commotion — charted in England.

“The card after that first Monarchs season is my favorite because we won the World Bowl,” Gelbaugh said. “Nothing matters as much as winning.”

Gelbaugh, now a salesman for a D.C.-area construction company, still receives a few autograph requests through the mail each month. His co-workers get a kick out of the requests. So does Gelbaugh, who enjoys signing the cards and sending them back.

“It’s crazy having cards still show up, given that it was damn near 30 years ago,” he said. “Sometimes it doesn’t even feel like that was me.”

The cards signify something special for the well-traveled signal-caller: “You were there, and nobody can take it away from you.”

***

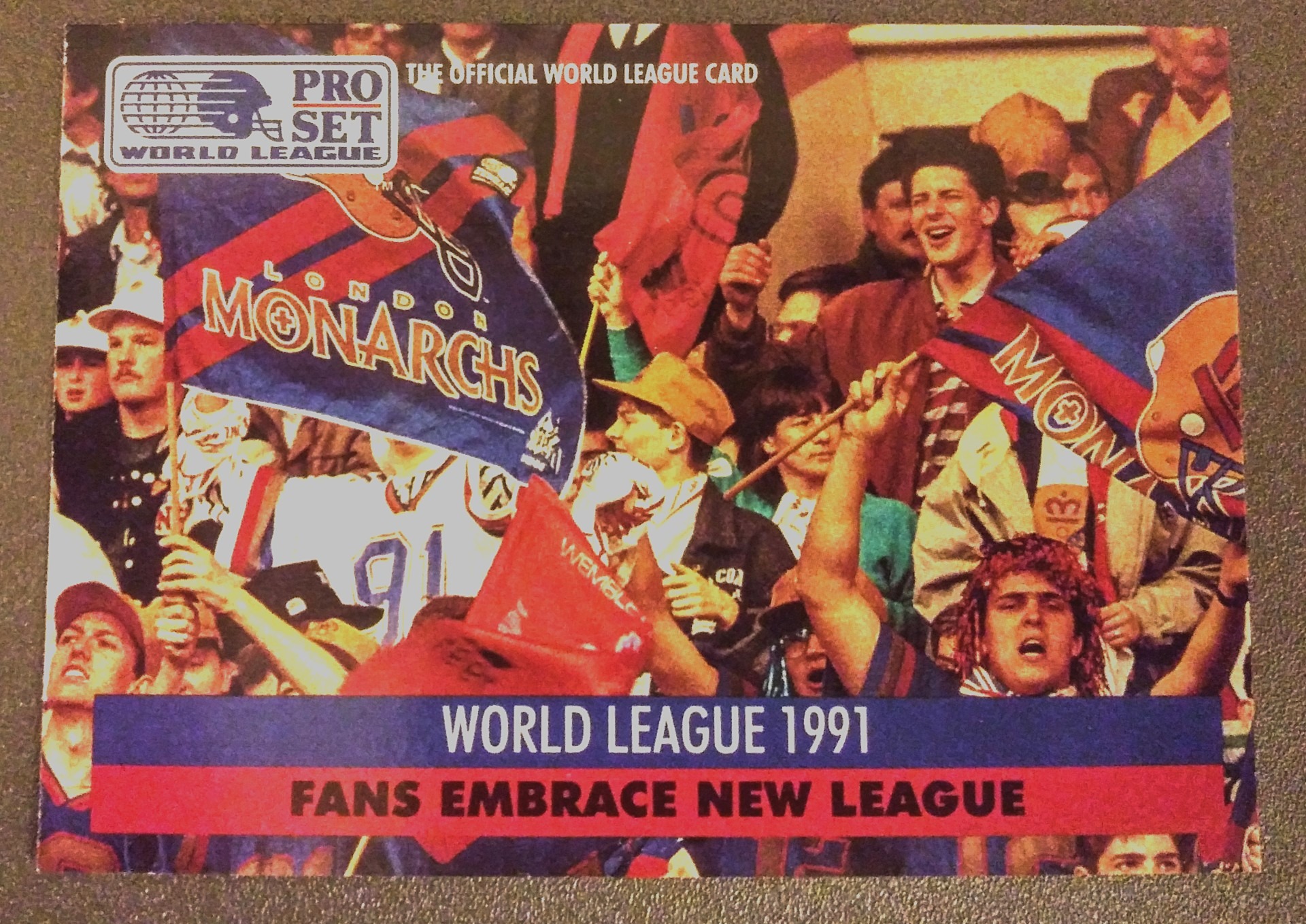

Early World League cards reflect the league’s growing pains and volatility.

After Pro Set celebrated the league’s kickoff, Ultimate and Wild Card produced WLAF sets of their own in 1992. Gone was the 0-10 Raleigh-Durham Skyhawks, which were replaced after the inaugural season by the Ohio Glory (which didn’t fare much better at 1-9).

Las Vegas-based Ultimate offered gimmicks galore, including a hologram and mini-poster tucked inside the lid of boxes, and a scratch-off giveaway for a $1 million prize or autographed cards of NFL stars Jim Kelly and Lawrence Taylor. All you needed to do was spell five letters on the scratch-offs, which were seeded one per pack: W-O-R-L-D.

Meanwhile, Wild Card, based in Ohio, featured stripe parallel cards — with numbers ranging from 5 to 1,000 — that could be traded for or redeemed, with 1,000 stripe cards the rarest.

Collectors and fans stateside mostly ignored the league, leading to paltry attendance figures and laughable TV ratings.

In September 1992, following the second World League season, the NFL owners voted to shelve the developmental league, which had lost tens of millions of dollars. The hiatus covered the 1993 and 1994 seasons.

The league returned in a different form 1995, with six teams based in Europe and the focus of expanding the NFL’s fan base in Europe while developing NFL-caliber talent.

***

After winning the World Bowl, Gelbaugh struggled to catch on in the NFL.

For one, he had to heal up from a separated shoulder and a hairline fracture in his left collarbone that he sustained while playing with the Monarchs. There was also a rule in place, later waived, that required an NFL team to double his World League earnings.

Gelbaugh eventually signed with the Phoenix Cardinals in 1991 and started three games. But he didn’t have the “Nasty Boyz” blocking for him and World League defenses to pick apart. Phoenix was a 4-12 team and Gelbaugh faced constant pressure in the pocket, compiling a 3-10 touchdown-interception ratio and a 42.1 passer rating. He was left unprotected after the season, too, and wound up being signed as a Plan B free agent by the Seahawks — whose offensive coordinator happened to be Kennan, Gelbaugh’s head coach in London.

And then Seattle reallocated Gelbaugh, along with his Monarchs teammates Theo Adams and Dedrick Dodge, back to London in the spring of 1992 to play another World League season. No rest, no time to heal, no off-season.

And no return to glory for the London Monarchs. The reigning World Bowl champs finished the season 2-7-1. Pinballing between the NFL and Europe took its toll on Gelbaugh.

“I went over there and got a concussion, I got a little dinged up. I was exhausted,” Gelbaugh said. He ended up sharing QB duties with Fred McNair, the older brother of former NFL quarterback Steve “Air” McNair.

Then it was back to the U.S. to join the Seahawks, who had two higher-profile and higher-paid quarterbacks — Dan McGwire and Kelly Stouffer — competing for the starting job. Gelbaugh was the steady, seasoned No. 3, “sort of a vagabond at that point in my career.”

After Stouffer and McGwire went down with injuries, Gelbaugh the vagabond ending up starting eight games for the Seahawks in 1992 and orchestrated a thrilling 16-13 overtime win on Monday Night Football against the Broncos on Nov. 30.

“I probably shouldn’t have even been suited up,” Gelbaugh said as he recalled the comeback. Two weeks earlier, against the Raiders, he blew out his knee. “I was all taped up with a big brace on my knee. They threw me in there with about five and a half minutes to go. Larry Kennan just said, ‘It’s your game. Call the plays, have fun.’”

The Seahawks were down late in the fourth quarter 13-6. As the clock wound down, Gelbaugh found James Jones over the middle for a completion. Jones was tackled at the 3-yard line. Gelbaugh rushed the offense to the line and spiked the ball. Three seconds left. Time for one final play.

Gelbaugh stepped back in the pocket and fired, finding Brian Blades in the end zone for a game-tying touchdown.

“Even though I haven’t played in 23 years now, people still think of me as the football player. I’ve been in sales longer than I’ve played football, but that’s how people still think of me,” he said.

***

Football is in their blood.

Three early stars from the WLAF came from the same family: Jason, John and Judd Garrett.

Jason, a QB, played for the San Antonio Riders alongside his older brother John, a wide receiver. Judd was a running back for the London Monarchs and led the league in 1991 with 71 catches.

All three brothers bounced around the pro ranks. Jason found the most success, serving as Troy Aikman’s backup during the mid-1990s with the Dallas Cowboys, where he won two Super Bowl rings. He became the Cowboys’ head coach in 2010.

Their father Jim was also a pro head coach, guiding the World Football League’s Houston Texans for 11 games in 1974. After the Texans’ owner ran out of money due to low attendance, the team moved to Louisiana and became the Shreveport Steamer. But instead of making the interstate move, Jim Garrett was fired by the WFL after calling the new destination “rinky-dink.”

While all of Jim Garrett’s sons would appear on cards in the early 1990s, the father’s first card would come decades later.

***

Score/Pinnacle created a 26-card set of WLAF cards in 1996 that included William “Refrigerator” Perry and Manfred Burgsmüller

When the World League returned in 1995, Score/Pinnacle was ready, developing a 26-card set in 1996. The set contained base cards and six motion cards devoted to “team leaders,” including William “Refrigerator” Perry, a star on the Super Bowl XX champion Chicago Bears, Kelly Holcomb, who became a starting QB for the Browns and Bills, and Manfred Burgsmüller, a longtime star of German’s Bundesliga soccer league who joined the Rhein Fire as a kicker at age 46 and continued playing for the team until 2002, when he was 52 years old.

The sets — sold in a single pack — were supposed to be the start of an ongoing partnership. “Look for expanded World League of American Football cards in April 1997,” a promo card inserted in the packs reveals.

Sadly, those cards, like many other Score/Pinnacle offerings, would never come. It wasn’t the first time a card set devoted to the alternative leagues was planned, then scrapped.

***

The July 7, 1974 issue of Sports Illustrated featured an interesting line about the upstart World Football League, which was siphoning off talent and attention from the NFL.

“Topps Chewing Gum Inc. is preparing bubblegum cards of WFL players. What more could you want?”

Richie Franklin didn’t want anything more. “I turned 13 exactly a week after Larry Csonka, Jim Kiick and Paul Warfield signed with the Toronto Northmen,” Franklin said. “I thought this thing was really gonna take off.”

As a teen, Franklin preferred the Charlotte Hornets. Since he lived in Virginia, he could pick up the team’s games on the radio. But he happened to like everything about the league.

Bill Jones, meanwhile, grew up in Anaheim, Calif., and his father took him to his first pro football game in 1974 — the WFL’s Southern California Sun, one of the league’s more successful teams.

“Here was this team in our backyard,” said Jones, who was transfixed by the “bright colors and cool uniforms.”

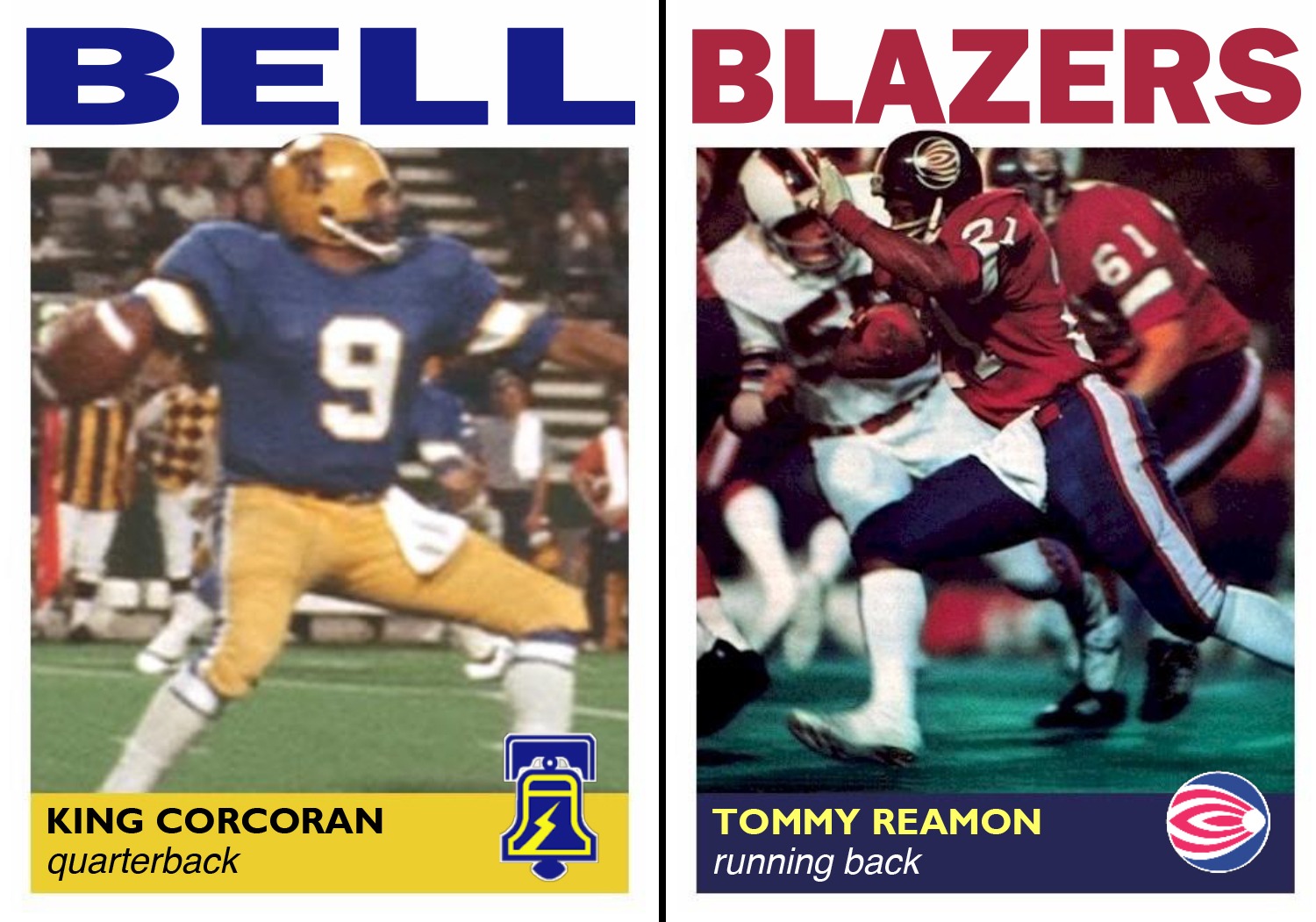

Cards from WFL stars “King” Corcoran and Tommy Reamon were long overdue, and were finally released in recent years.

The WFL had colorful players, too. Jim “King” Corcoran, the Philadelphia Bell’s flamboyant, womanizing QB, had a cannon for an arm and an ego to match. Tommy Reamon, who spurned the Pittsburgh Steelers to join the Florida Blazers because he wanted to play instead of waiting his turn and backing up Franco Harris, rushed for 1,576 yards and scored 14 touchdowns in 1974, carrying the Blazers to the World Bowl despite the team’s players going months without getting paid.

Bounced checks and empty promises were a problem across the league. The league’s owners pledged big money for high-profile players but then didn’t have the money to pay salaries when attendance dropped. Two teams — the Jacksonville Sharks and Detroit Wheels — shut down during the 1974 season, while the New York Stars and Houston Texans relocated to Charlotte and Louisiana.

The league got desperate. Ahead of the 1975 season, the WFL tied its future to signing Joe Namath and offered the superstar Jets QB a $4 million contract — a $500,000 signing bonus and three-year contract for $500,000 a year, plus a $100,000 pension for 20 years, a percentage of TV revenue, and possible partial ownership of a nonexistent team in New York.

Namath, of course, ended up resigning with the Jets. WFL President Chris Hemmeter admitted at the time that missing out on Namath “may be a tremendous setback in TV negotiations … But on the other hand, it may be a plus factor because we have established in the sporting community that the league will not compromise its principles.”

WFL’s national TV partner dropped its coverage after the Namath deal fell through, and on Oct. 22, 1975, 12 weeks into its second season, the World Football League ceased operations. Memphis and Birmingham, the WFL’s strongest and best-run franchises, applied to the NFL, hoping to become expansion teams, but instead franchises were awarded to Seattle and Tampa Bay.

Topps never ended up making its WFL bubblegum cards, and beyond photographing some of the players in their WFL teams, it’s unclear how much planning went into the cards

(L to R): Alfred Jenkins, WR, Birmingham Americans, Tommy Reamon, RB, Florida Blazers, Charlie Bray, OT, Memphis Southmen (courtesy of Richie Franklin)

before they were scrapped.

Franklin’s love of the WFL never diminished, and he devoted his efforts to preserving the league’s history, collecting everything he could find related to the World Football League.

Jones, meanwhile, was reacquainted with the WFL after buying artwork to make gumball helmets for the league’s teams. He’s since made gumball helmets reflecting every WFL helmet variation and for lots of other lost football leagues.

Through Flickr posts about his gumball helmets, Jones connected with another football fan, Willie O’Burke, and the pair started creating virtual cards for the WFL and teams from other defunct leagues. Greg Allred, an Alabama native who like Franklin was a student of the league’s short but memorable history, made the foursome complete.

Franklin’s collection included Topps slides of players in their World Football League jerseys, as well as images from photographers and private collections.

“When those negatives were coming up on eBay, we got to talking about how nice it would be if we could do a set,” Franklin said.

The friends were interested in creating the types of cards that Topps never finished. So they got to work, developing a first series of WFL cards in 2013 devoted to the 1974 season.

Corcoran, Reamon and Jim Nance, the Texans/Steamer fullback and 1966 AFL MVP, were included in the series. Four more series have followed, along with subsets devoted to topics such as team logo helmets, schedules, quarterbacks and action cards. The group’s latest release highlights all of the 27 head coaches of the WFL, even if they only coached one game. Jim Garrett, the former Houston Texans head coach, is in the set. Just don’t call it “rinky-dink.”

The cards have the feel of mid-1970s Topps releases, down to the vintage paper stock — the closest thing you’ll find to the real thing.

Jones and O’Burke typically focus on the card fronts, settling on potential designs and sending them to the others for input. Franklin and Allred work on the card backs, deciding on how much space will be devoted to the players’ stats and bios and how best to tell each player’s story. Other contributors include graphics designer Steve Liskey and graphic artist Gene Sanny.

The operation is guided by four friends scattered across the country, connected by their shared love of a football league that disappeared nearly 45 years ago, trying to recreate a lost piece of their childhoods.

“We knew there were other WFL fans out there like us. We wanted the cards ourselves because we never got to collect them in the 70s because Topps didn’t make ‘em,” Franklin said.

“It’s something we don’t want people to forget.”

The players are appreciative that someone didn’t forget. At this point more than two dozen WFL figures have taken photos holding their cards for the WFL Cards website, including league commissioner Gary L. Davidson and Vince Papale, the Philadelphia Bell player whose story inspired the Mark Wahlberg movie “Invincible.”

Reamon is pictured too, finally holding his card all those decades after a Topps photo shoot captured his younger self, the brash back who just wanted to play. For Reamon, what more could you want?

***

The WFL-addicted friends recently released a card set devoted to another memorable, long-gone league: the United States Football League of the mid-1980s.

The USFL may have had the most talent of any of the defunct leagues. Players like Jim Kelly, Steve Young, Reggie White and Gary Zimmerman made their pro debuts in the USFL, while college stars Doug Flutie and Herschel Walker picked the USFL over the NFL, lured by massive contracts, the promise of playing immediately, and the energy of something new.

It didn’t hurt that the USFL — which played in the spring and summer — had some fun, colorful owners, including a fast-talking real estate scion named Donald Trump who saw the New Jersey Generals as a way to build his national profile.

After failing to make WFL cards, Topps jumped at the chance to create box sets for the USFL in 1984 and 1985. The cards are reflective of their era, featuring a mix of posed and sideline photos, along with pink tones on the reverse and the texture of typical Topps sets of the 1980s. The 1984 cards feature “USeFuL facts” boxes on the reverse: “Stars’ team colors: Crimson, old gold, and white.” Thanks.

The sets aren’t flashy, but they hold up because of the players represented and lore around the league. The flashy play, the amount of talent, the desire to be taken seriously.

Trump’s ill-conceived plan to move the USFL to the fall brought an early end to the league, and the $3 damages awarded in an antitrust case against the NFL marked its death sentence. But the USFL’s spirit — not so much the Spirit of Miami, a planned team that never played — lives on in the Canton-bound careers the league launched.

***

By the late 1990s, the World League of American Football — then known as NFL Europe — had established itself as a legitimate feeder league, developing talent that would reach the apex of the football world stateside.

A former supermarket shelf-stocker and Arena Football League star cemented that legacy after playing for the Amsterdam Admirals.

Kurt Warner was sent to Europe by the Rams in 1998, sharing roster space with Jake Delhomme, another QB who reached the Super Bowl.

Warner entered 1999 training camp backing up Trent Green, but after Green went down with an ACL tear, Warner got his chance, leading an offense that featured Marshall Faulk, Isaac Bruce and Torry Holt. Behind Warner, “The Greatest Show on Turf” was born.

Warner passed for 4,353 yards and 41 touchdowns that season, winning the NFL MVP and guiding the Rams to the championship in Super XXXIX.

Warner’s overnight success brought renewed interest to NFL Europe, especially on cardboard. Numerous 2000 releases devoted checklist space to emerging NFL Europe stars on the chance that Ron Powlus, Pepe Pearson or Danny Wuerffel would become the next Warner (they didn’t).

Topps Finest, meanwhile, highlighted 10 players who made it stateside after playing in Europe, a before-and-after look at the impact of the transitional league. Warner appeared in the insert set alongside players like La’Roi Glover, Damon Huard, Brad Johnson, Delhomme and Jon Kitna — an impressive list for anyone who doubted NFL Europe’s impact.

Their successes came as the NFL embodied its nickname as the “No Fun League,” penalizing and fining players for on-field expressions such as the “throat slash” gesture or taking off their helmets after touchdowns.

Where alternative leagues fuel innovation — such as the USFL’s option for two-point conversions after touchdowns, adopted a decade later by the NFL — the “No Fun League” had become basic and stale.

A fun, edgy version of pro football? That could be something.

***

Every conversation about the XFL begins and ends with one phrase: “He Hate Me.”

Rod Smart, a running back out of Western Kentucky University, appeared in training camp with the Chargers in 2000, but was released. With no NFL teams calling, Smart joined the Las Vegas Outlaws of the XFL (the X, while thought to represent “Xtreme” or “extra fun,” didn’t actually stand for anything).

The XFL, created by WWE chairman and CEO Vince McMahon and NBC executive Dick Ebersol, took aim at the stodgy NFL. Instead of a coin toss, a player from each team participated in a “scramble” — a race to recover a football (Orlando Rage DB Hassan Shamsid-Deen dislocated his shoulder that way). Overhead cameras gave the broadcasts a video game feel. Behind-the-scenes footage showed players and cheerleaders in non-game settings.

Players could also choose personalized names for the backs of their jerseys. So Smart became “He Hate Me,” a callout to his detractors and opponents, and Los Angeles lineman Jerry Crafts, formerly of the Buffalo Bills, went by “Big Daddy.”

Well, just about everything.

First, the gameplay was boring, far inferior to the NFL or even major college football. The oversexualization of the cheerleaders didn’t help, either. The most widely ridiculed stunt teased a

video camera being placed in the cheerleaders’ locker room during halftime. The segment devolved into a dream sequence featuring the cheerleaders playing Twister and the photographer — wearing a jersey reading “She Love Me,” naturally — being pampered, along with Rodney Dangerfield appearing in a towel.

Advertisers bailed on the league. After more than 25% of viewers vanished week over week, the league began giving away free time to advertisers.

Topps’ XFL card set hit shelves in the spring of 2001 at the tail end of the league’s first season. Ahead of the release, Topps reportedly produced 200,000 promo packs for distribution at home openers, wrestling events, and for customers who bought merchandise on XFL’s website. The company also planned a print campaign in Tuff Stuff and other publications.

Topps hoped the league would become a major success. The 100-card XFL set reflects the adolescent fan base the league hoped to cultivate, with a 16-card cheerleaders subset called “Girls on Fire.” Yes, 16% of the set was devoted to cheerleaders, and the writing on the card backs could have doubled as unused pickup lines from 1980s dating videos.

“Kiushin, a bodybuilder, wants to open her own dance studio. Sign us up for lessons.”

“The reigning Miss Little Rock wants to pursue a career in public relations. We respectfully suggest meteorology instead. We just love Sunni weather.”

“When she’s not cheering on the Maniax, she’s a substitute high school math teacher. We can do the numbers, Cicely. And we like them.”

One company that didn’t like the numbers — Topps. Within months of Maddox leading the Los Angeles Xtreme to a 38-6 victory in the Million Dollar Game (yes, that’s what they called the championship), Topps and the rest of the world was ready to move on from the XFL. The X may as well have stood for Xtinct.

“It wasn’t big enough to call a disaster, but I expect we won’t come out positive on the XFL,” Topps CFO Catherine Jessup told Bloomberg at the time. “How much we could lose off the XFL we won’t know until dealers return their stock.”

***

You think they would have learned.

Charlie Ebersol — the son of the XFL co-founder and himself the director of the ESPN “30 for 30” documentary on the league, “This was the XFL” — thought he figured out how to make a spring league work. He pitched the plan to former NFL GM Bill Polian, who came on board.

The league had a catchy name: Alliance of American Football, or AAF. They recruited football icons to lead the teams and found owners committed to the long haul.

The franchises, positioned in football-thirsty cities such as Birmingham, Memphis, Salt Lake City and San Diego, recruited talented players wishing to return to the NFL, like Trent Richardson, and other players ready to break out.

Who cared if the NFL wasn’t directly connected, at is had been with NFL Europe? That league went away for good in 2007, fading with a whimper, a shadow of the days of Stan Gelbaugh and Kurt Warner.

A 2019 Topps Now card showing San Antonio Commanders linebacker Shaan Washington’s sack of San Diego QB Mike Bercovici.

The AAF would be different, a way to escape the stodgy shield and its many scandals, some fueled by the former USFL owner inhabiting the White House.

All you needed to see was one card to recognize that AAF wasn’t the NFL — a Topps Now card showing San Antonio Commanders linebacker Shaan Washington’s sack of San Diego QB Mike Bercovici on Feb. 9, 2019, the league’s opening weekend. Washington and Bercovici are parallel to the ground, the quarterback’s helmet flying. The picture is violent and vicious — a callback to the football’s not-so-distant past and something an image-conscious NFL would never approve today.

The card sold 736 copies on Topps’ website, making it the most popular of the 43 print-to-order cards from Topps’ online set.

The AAF embraced its role as a renegade league and the history that had come before. During a broadcast for a game between the Atlanta Legends and Orlando Apollos, CBS showed color TV analyst Gary Danielson’s WFL Series III card — one of the cards created by the four friends keeping the World Football League alive on cardboard. Danielson played for the Stars/Hornets in 1974 and Chicago Winds in 1975.

Within weeks of the start of the AAF season, the same old problems began cropping up. Spiraling expenses, corporate infighting, tepid fan support, players worried about their employment prospects.

After seven weeks of football — and soon after Topps released its first AAF series — the league was history.

Opening a box of 2019 Topps AAF remains a curious experience months after the league folded. The cards reflect the league’s newness and optimism. Some of the players are depicted in the midst of practice and game action. Others are seen in winter outfits, photo ops in Starter gear, and you momentarily confuse the set for a clothing catalog.

Numerous players appearing in the AAF set are currently competing for spots on NFL rosters. Scrappy safety Derron Smith, who starred for the San Antonio Commanders, is hoping to land with the Vikings, as is former Salt Lake Stallions defensive end Karter Schult.

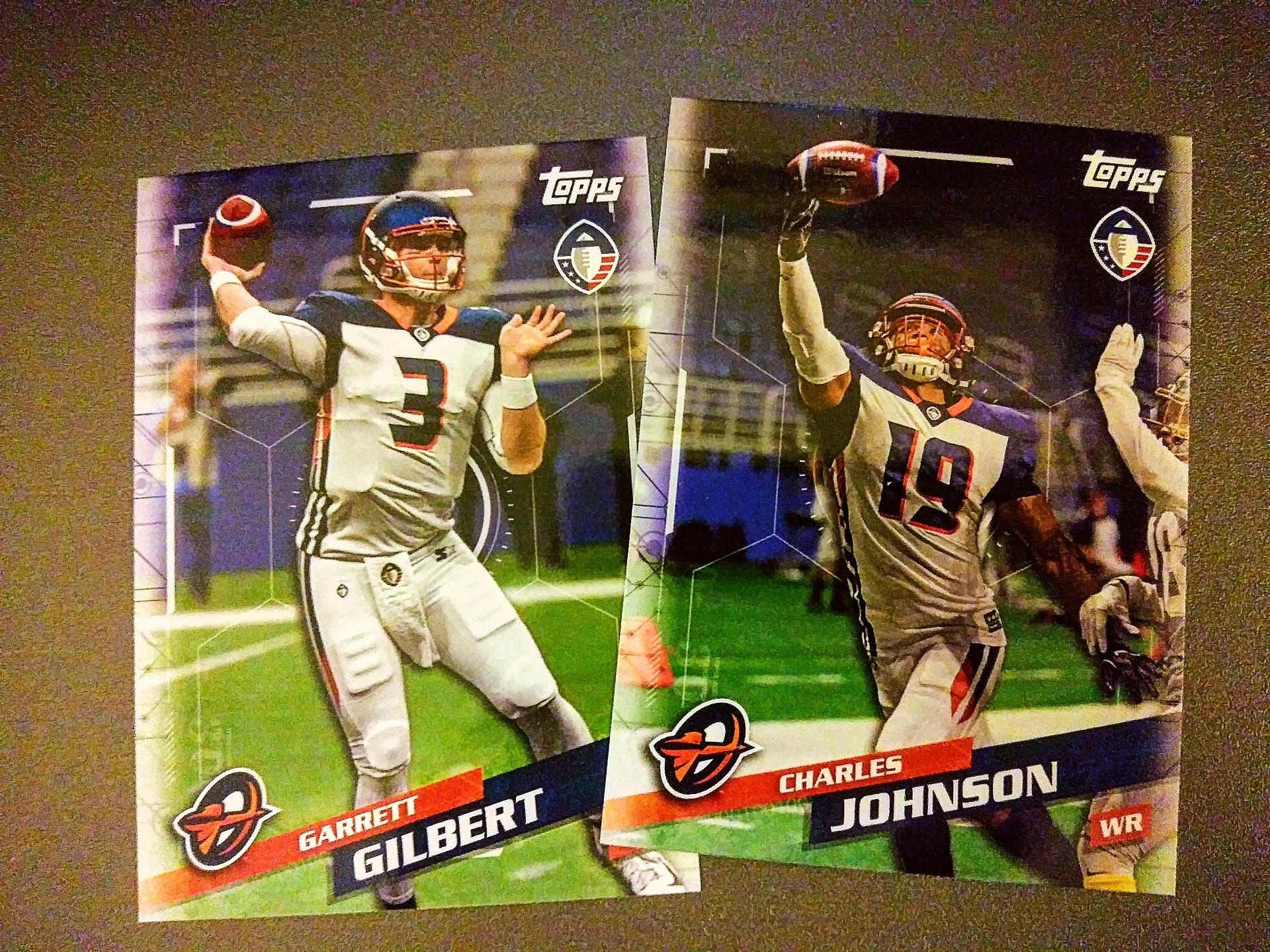

Garrett Gilbert, the Orlando Apollos QB, is gunning for a spot with the Browns, while his favored target, Charles Johnson, signed with the Eagles.

Rashad Ross, one of the AAF’s other leading receivers, is vying to return to the NFL for the Panthers.

Football mainstays make their appearances in Topps AAF, too — Mike Singletary and Troy Polamalu and Daryl “Moose” Johnston and Michael Vick and Steve Spurrier, who decades earlier was coaching the USFL’s Tampa Bay Bandits.

And then there’s Mike Riley. The San Antonio Commanders head coach is seen staring upward on his Topps AAF card, seemingly pondering what he did in a past life to deserve this

assignment.

A quarter century ago Riley was photographed coaching for another blink-and-you-miss-it San Antonio team, the Riders of the World League of American Football, for the final card in Pro Set’s 1991 WLAF box set.

After the AAF’s demise, Riley found a new gig — offensive coordinator of the XFL’s unnamed Seattle franchise when the league relaunches in 2020. There’s optimism that the upcoming league will succeed where other leagues failed.

Gameplay should be better than the XFL’s previous iteration, when “He Hate Me” jerseys were all the rage, and there won’t be any cheerleaders this time.

Maybe it will work?! History isn’t on the XFL’s side, but fans of alternative football leagues remain hopeful. Whatever the outcome, the cards will live on — reminders of football dreams that far outlasted the leagues that helped to keep them alive.

The Leagues Are Long Gone, But The Cards Live On

For more from Dan Good, follow him on Twitter @Dgood73.

- The Story Behind CC Sabathia’s First Card - October 25, 2019

- The Montreal Expos are Finally in the World Series, but it’s 25 Years Too Late - October 21, 2019

- Topps Magazine Back in Print! - August 26, 2019